ANALYSIS: ‘There’s No God Down Here’: Maternal Absence and Abjection in ‘Sanctum’

In her gender analysis of Aliens (1986) Barbara Creed notes how the “dark and slimy” interior spaces of the Alien Queen’s egg chamber “offer a nightmarish vision of what [Julia] Kristeva describes as ‘the fascinating and abject inside of the maternal body’” (1993:51). The mise-en-scène of Aliens (where this viscous-coated lair is contrasted with the steel structures of the colony base) thus reproduces the narrative conflict between the Queen (nature) and Ripley (culture), and reiterates the abject threat posed by the former. For Creed, the visual design of Aliens (and the film’s representations more generally) brings its audience into a confrontation with the repressed content associated with the maternal: the horrors of birth, the monstrous body and the trauma of separation.

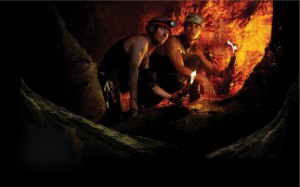

Sanctum, a film shot almost entirely within dark cavernous underwater spaces, provides a recent example in which the mise-en-scène can be interpreted through reference to the maternal abject. While the association of James Cameron (director of Aliens) to Sanctum – he’s credited as Executive Producer – is perhaps more by coincidence than design, both films provide an interesting point of comparison in the construction of gendered-space. However, unlike Aliens, which focuses on a conflict of ‘mothers’ (surrogate vs. alien), in Sanctum the maternal figure is noticeably absent.

Sanctum, a film shot almost entirely within dark cavernous underwater spaces, provides a recent example in which the mise-en-scène can be interpreted through reference to the maternal abject. While the association of James Cameron (director of Aliens) to Sanctum – he’s credited as Executive Producer – is perhaps more by coincidence than design, both films provide an interesting point of comparison in the construction of gendered-space. However, unlike Aliens, which focuses on a conflict of ‘mothers’ (surrogate vs. alien), in Sanctum the maternal figure is noticeably absent.

Set in Papua New Guinea, Sanctum details the attempts of a team of explorers to escape from a vast network of subterranean caves (Esa-ala) in which they become trapped. But what initially appears as a tale of group survival gradually reveals itself as a narrative of father-son reconciliation. On leave from his mother, Josh (Rhys Wakefield) has begrudgingly joined his expedition team-leader father Frank (Richard Roxburgh) in PNG. Angered by his dad’s steely and unforgiving attitude the relationship between Josh and Frank is cast in clearly antagonistic terms. Josh resents his father’s absence from the family home and Frank is unwilling to accept his son’s irresponsible behaviour. It is only when they become trapped underground, and united in the struggle to survive, that the pair are forced to put to rights their differences.

But in a narrative where the mother is absent, the only other female characters are granted little influence, and father-son survival is priority, the caves stand as a symbolic reminder of this threatening maternal presence. As Sanctum makes clear, Frank has abandoned his family for these underground expeditions. The caves function symbolically as a female/maternal substitute, while Josh’s mother, who retains custody, stands (like the caves) as a literal physical impediment to the father-son relationship. But beyond the abject symboli sm (the dark and slimy interiors) and the obvious maternal substitution, Sanctum links the caves to the ‘mother’ in other ways. Associating Esa-ala with the incomprehensible force of mother nature Frank reminds his son at one point that, “there’s no god down here”. In the absence of God (qua patriarchy) Sanctum reiterates the traditional binary where woman/nature is situated in opposition to man/culture. The goal of escape (to conquer Esa-ala) is inseparable from the film’s gender subtext.

sm (the dark and slimy interiors) and the obvious maternal substitution, Sanctum links the caves to the ‘mother’ in other ways. Associating Esa-ala with the incomprehensible force of mother nature Frank reminds his son at one point that, “there’s no god down here”. In the absence of God (qua patriarchy) Sanctum reiterates the traditional binary where woman/nature is situated in opposition to man/culture. The goal of escape (to conquer Esa-ala) is inseparable from the film’s gender subtext.

It’s relevant then that in Sanctum’s closing stages, when father and son appear reconciled and escape appears likely that this cavernous underground is recast in more masculine terms. Justifying his abandonment of the family, Frank confesses that (in contrast to his earlier god-less assertion) the caves are “his church”, his domain. In doing so, Frank reorients the threatening spaces of the film from their abject maternal association to a scene of paternal triumph, achieved in part through the reconsolidation of the father-son bond. It is only by conquering the maternal spaces of this dark underworld – by reasserting the primacy of the paternal – that freedom can be achieved through the return to the surface. Not surprisingly, the world the son returns is one in which the father (and not the mother as before) is centrally important. As Josh remarks of Frank in the film’s closing voice-over, “He was a helluva fella…once you got to know him”.

In light of the film’s gender politics, it is perhaps something of an irony that Sanctum is at its most compelling during the sequences in which the group silently negotiate the cramped water-filled crevices of the cave network. By contrast, the moments where the film pauses for discussion amongst the explorers,  particularly between father and son, are repeatedly undermined by excruciating, ham-fisted dialogue. Even as the caves are presented as a threatening obstacle to survival, they represent the film’s singular remarkable characteristic. Ultimately, this is not enough to prevent the film from jettisoning the maternal (in a figurative comparison to Ripley’s ejection of the Queen into outer-space in Aliens) but it does render Sanctum’s parallel worship of the father a rather trite and forgettable experience.

particularly between father and son, are repeatedly undermined by excruciating, ham-fisted dialogue. Even as the caves are presented as a threatening obstacle to survival, they represent the film’s singular remarkable characteristic. Ultimately, this is not enough to prevent the film from jettisoning the maternal (in a figurative comparison to Ripley’s ejection of the Queen into outer-space in Aliens) but it does render Sanctum’s parallel worship of the father a rather trite and forgettable experience.

*Creed, Barbara (1993), The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, Routledge, London & New York

Intriguing analysis, Josh. I wonder where Kubla Khan fits into this reading? Frank teaches the poem to Josh as a symbol of reconciliation – from memory they don’t get beyond the fifth line, but Coleridge’s imagery is so rich, I’m curious if it would assist your analysis of the caves as a maternal substitute?

If memory serves again, I believe Kubla Khan was supposed to be Frank’s ex-wife’s (Josh’s mum) favourite poem. Curiouser and curiouser…

You raise a really good point in terms of the poem, Alice. I’ve been pondering that too – although I find it a little hard not to disassociate the work from the News on the March sequence towards the beginning of ‘Citizen Kane’.

I can’t help but wonder whether the film is using the Coleridge’s vivid description of space in Kubla Khan (which approaches mystical proportions) to parallel to the men’s investigation/colonisation of the cavernous (and equally mystical) regions of Esa-ala: the repeated images of the shaman may further reinforce that reading.

That Frank recites the poem as a pretext for father-son bonding also reorients its ties to the maternal figure and grants it a paternal significance.

In terms of the both its spatial symbolism and gender association, perhaps the poem functions as yet another example where ‘Sanctum’ seeks to substitute the mother (and all that she signifies) in preference of the father.